Back in 2004 or thereabouts, after I’d left Wessex Archaeology and before I started my Eternal Idol site, I wrote a book on Stonehenge provisionally entitled A Glimpse of the Great Beyond, a work based on my absolute conviction that one didn’t have to rely on archaeological excavations at the ravaged, desecrated site to be able to say new and original things about the ruins and their distant origins.

Glancing at the first chapter, I’m satisfied that it holds up all these years later, despite the many things that have been written and said in the intervening time about the mysterious monument on Salisbury Plain. I’ll reproduce a small excerpt from Chapter I here and I’ll leave it to others to decide for themselves what they think, while part of it has some bearing on what follows later in this post:

Why has no one yet successfully transported a bluestone from south Wales to Salisbury Plain using agreed prehistoric methods? We have the manpower, we have the flint axes for cutting down trees to fashion into rollers and rafts, we probably have the intelligence, the physical strength and the ingenuity, we have ropes and we have grease. We have everything we could possibly wish for aside from one vital ingredient, which is passion, because no individual or group of people today is sufficiently motivated to recreate the journey of one of the bluestones or sarsens, let alone attempt to reconstruct the entire monument using prehistoric methods.

The word ‘passion’ comes from the Latin verb ‘patior’ meaning ‘I suffer’, so in this context, I would define passion as the capacity to voluntarily endure hardship or suffering towards a greater end, while being fully aware that there is no absolute guarantee of success. So, right at the beginning of our quest, we can now point without question to one intangible, abstract but nonetheless very real quality that our ancestors possessed specifically with regard to Stonehenge.

Identifying this element is all well and good, but does it have any practical application that will assist in enabling us to reach the solution we seek? Out of pure curiosity, let us say, do any practices exist today that not only have their basis in antiquity, but also involve passion in the literal sense we’ve described? One such tradition immediately springs to mind and it is the modern Olympic marathon.

To win this race is arguably the pinnacle of human sporting achievement and it is easy to understand why, as anyone who has watched the agonized faces of the runners can testify. These people voluntarily put themselves through the extremes of human endurance during the race, while training relentlessly in a Spartan regime for years beforehand. And why do these men and women choose to suffer so? For the chance of glory and to demonstrate what humans are capable of achieving in a strictly delineated field; in this case, that of long distance running.

The marathon was never an event in the ancient Olympic games, but was reintroduced in modern times in memory of Pheidippides, who was said to have run the twenty-six miles back from the battlefield of Marathon to Athens in 490 BC to proclaim that the Persians had been defeated. Once he’d announced the victory, he collapsed and died and little wonder, given the heat, the length of the journey back, the difficult terrain he had to cross and the fact that he’d just fought a desperate pitched battle against an invader superior in numbers.

This is the story that we accept and rejoice in today, but the likely truth is even more astonishing, because the tale of Pheidippides running the twenty-six miles or so to Athens was a later version. The Greek historian Herodotus, writing closer to the time, relates that Pheidippides actually ran from Marathon to Sparta before the battle took place to request assistance from the Spartans and he is said to have covered one hundred and fifty miles in two days, a vast distance even by the standards of our modern athletes. Going on the evidence of this account, the accomplishments of our ancestors were even more impressive than we sometimes suppose.

The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Second Edition, describes the death of Alexander the Great in the following lyrical terms “In him the soul wore out the breast and he died, in his thirty-third year, of a fever which might well have spared him had he ever known how to spare himself.” I would suggest that very much the same thing applied to the demise of Pheidippides, but despite the risk of injury or even death, our modern athletes continue to be inspired by the sheer passion displayed by this dead hero, regardless of the real route or the exact distance covered. They continue to run the marathon and will almost certainly do so for centuries to come, because the prize for triumph is so great and so alluring.

It would be as well to bear in mind this potent element of passion when considering the reasons that Stonehenge was erected. Nearly two and a half thousand years after the death of Pheidippides, the whole world still remembers his name, the name of the battlefield from whence he came, the route that he took and the reason he ran it, despite his doubtless real suspicion that this feat would almost certainly result in his own premature death.

A natural consequence of an act of true passion such as the run of Pheidippides, whatever course it took, is that onlookers should react with wonderment to what was achieved by a human being. Even today, we still marvel at Pheidippides’ remarkable feat and we are roused to admiration and occasionally to awe by the efforts of those who seek to emulate his triumph, nearly two and a half thousand years later.

And so it is with Stonehenge. Whether or not we consciously recognize the process, we still stand gazing at a monument, which, if it possesses anything, retains the power to evoke wonderment among us. We may not know the names of those who built it and we may know next to nothing about the precise degree of exertion and labour involved, but we recognize that our ancestors chose to make a truly colossal effort over a long period of time and stoically endured hardship in expectation of something wonderful as a reward for their efforts. In brief, we still appreciate the scattered remnants of an act of true passion when we see it, even if the event itself took place thousands of years ago.

Back to the main theme of my post. The third chapter of my unpublished book was dedicated to an intimate study of Geoffrey of Monmouth, author of Historia Regum Britanniae, or The History of the Kings of Britain, in which he described in precise detail how Stonehenge was built and how it came to be built. I long ago lost count of how many times I went into minute and exhaustive detail about all this in the pages of Eternal Idol, so I won’t bother repeating any of the material or arguments.

However, in the unpublished book to which I’m making reference here, I estimated that the odds of Geoffrey of Monmouth being right in his assertions through mere chance were something like 1,555,200 to one, although I believe this is an insanely conservative estimate and its inner workings will be obvious to anyone who’s chosen to familiarise themselves with the details of the subject matter.

I’m no statistician, but even if I’m 99% wrong, which I very much doubt, then Geoffrey still had a less than one in fifteen thousand likelihood of correctly ascertaining the origins of Stonehenge by chance, which surely means that any sane, reasonable or scientific person should consider that another agency was responsible for Geoffrey being correct. And just before I come to my main point, what of the name of this man? Geoffrey of Monmouth?

I would say it’s inescapable that Geoffrey had some strong link with this town, regardless of what form this link took. Perhaps he was born there, or perhaps he was educated there, as was I in the 1970s. There are numerous other possibilities, but to put it in its most basic form, Geoffrey of Monmouth was disturbingly accurate about Stonehenge and its origins as far back as 1136 AD, while this great man’s name is a clear testament to a significant connection he had with the town of Monmouth.

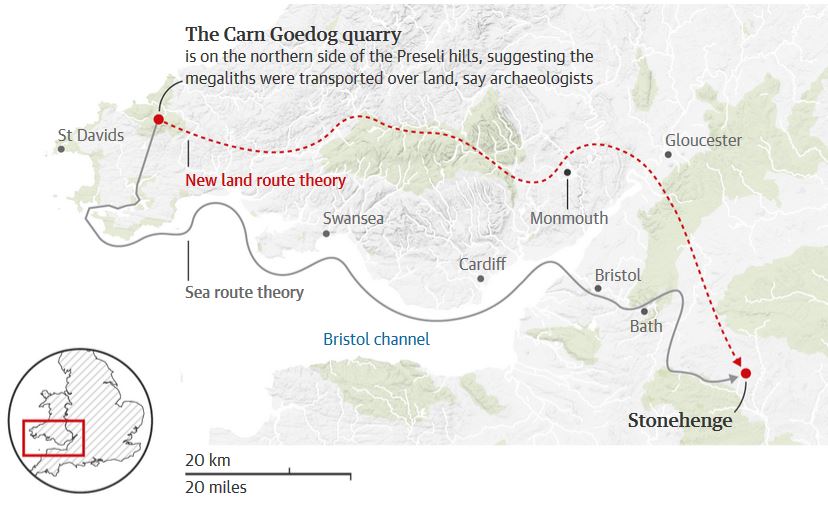

Imagine my intense surprise, therefore, when I read this intriguing article in the Guardian newspaper, in which a number of eminent archaeologists of my acquaintance express their belief that the bluestones were moved from West Wales to Stonehenge by a land route, which passed with a stone’s throw of what is now the town of Monmouth.

Who could ever have imagined such a thing? That what was effectively Stonehenge itself once laboriously passed within spitting distance of a place intimately connected with a man who later wrote with such insight about how and why the monument was moved? In a land, furthermore, that the Romans later described as belonging to the Silures tribe, people whose name may well have meant “The Men of the Stones” or something similar.

I’ve found all these details and many more to be engrossing for decades, for reasons I’m sure I needn’t spell out, but it seems I’m alone in this. Nowhere will you find a mention, let alone an examination, of these strange matters; my former colleagues the archaeologists are resolutely not discussing them, nor is a single member of the “online” Stonehenge community, but I’m not complaining – far from it.

One day, I will explore this matter in the most minute detail in a book I’m currently working on, which is provisionally entitled Hidden in the Hills, which deals with this and with related matters. Until such time as I’ve completed it, you are all of course at liberty to look into the matter for yourselves and to draw your own conclusions.

For now, I can only wonder at the precise nature of the bizarre mindset that stops archaeologists from so much as remarking on the astonishing apparent coincidence of stones that went on to become a part of Stonehenge passing so close to the site of Monmouth, a town itself intimately linked with a mediaeval chronicler who was famous for going into great detail about the long ago construction of Stonehenge.

A reasonable, impartial person might think that Geoffrey of Monmouth’s supposedly fabulous account of the construction of Stonehenge would be lauded and closely re-examined in light of the latest archaeological revelations that an ancient ‘road to Stonehenge’ passed so closely by the site of the town with which Geoffrey was so closely linked, but not a bit of it. Furthermore, this wilful ignorance and silence persists, as we can see by examining the contents of this BBC link dealing with discoveries linked to the 5,000 year old monument of Newgrange.

You can of course read it for yourself at your leisure, but in brief, an examination of the DNA of an adult buried at the monument has revealed that his parents were “first-degree relatives, possibly brother and sister.” One might think this is a fantastic revelation, brought to us in the 21st century exclusively by the wonders of science, but the BBC article contains more:

“Remarkably, a local myth resonates with both the DNA results and the Newgrange solar phenomenon. The story was first recorded in the 11th Century AD – four millennia after the construction of Newgrange – and tells of a builder-king who restarted the daily solar cycle by sleeping with his sister. The Middle Irish place name for the neighbouring Dowth passage tomb, Fertae Chuile, is based on this lore and can be translated as “Hill of Sin”.”

So, it seems that where writers of myth, fantasy, legend and folklore venture, then follow on the intrepid scientists and archaeologists, even if they’re a thousand years or so late in the search for some insight into the far-off origins of these mysterious ruins. And finally, in case anyone reading this has the slightest doubt about what I’ve written, or about the title I’ve chosen to given it, here’s an entirely apposite quote from Carl Sagan, one of the finest scientific minds Mankind has ever produced:

“What an astonishing thing a book is. It’s a flat object made from a tree with flexible parts on which are imprinted lots of funny dark squiggles. But one glance at it and you’re inside the mind of another person, maybe somebody dead for thousands of years. Across the millennia, an author is speaking clearly and silently inside your head, directly to you. Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people who never knew each other, citizens of distant epochs. Books break the shackles of time. A book is proof that humans are capable of working magic.”

[Cosmos, Part 11: The Persistence of Memory (1980)]

One reply on “Stonehenge’s Neglected Origins”

Glad to see you enjoying good health and bringing back Eternal Idol. There an interesting item in Guardian Online today (20.8.25.) saying that the tooth of a cattle skull found at Stonehenge came from Wales, raising the possibility that cattle were used to bring the stones to Stonehenge. So naturally I thought of you.